Selling out without selling out

Growing up a disgruntled ‘90s teenager whose heroes were Kurt Cobain, Ian MacKaye of Fugazi, and recording engineer Steve Albini, there was no greater crime against humanity than selling out.

Selling out meant selling your soul and values to get rich and famous. Creating art was about self-expression and doing what you wanted to do. Creating art to get rich was shallow and lame — selling out.

Some might critique this as a privileged position (which from a global perspective it certainly is), but the energy comes from an egalitarian, working class spirit. If we all work hard and stay true to where we come from and the scenes we’re a part of, the thinking goes, we’ll succeed against the monotonous drudgery of mainstream culture and make more interesting worlds of our own. The trick is to not sell out.

Fast forward three decades and nobody talks about this version of selling out anymore. The whole line of thought has vanished. Why? Because the world has already been sold.

Wealth inequality, increasing social precarity, the expansion of the market into more areas of life, and huge jumps in the cost of living changed not just the economics but the vibes of modern existence. Claire L. Evans from YACHT puts it perfectly: “Sometimes it feels like your life is a job and your house is a store.” This is what it feels like in a world that’s already been sold.

For creative people this hits especially hard as social media’s invention of “personal brands,” “influencers,” and the “Creator Economy” turned the few remaining aspects of life that hadn’t yet been marketized into the last ways we could make a living without working for somebody else. Gradually and then suddenly creative people found themselves doing little but selling: selling ourselves, selling our work, selling our hobbies, selling anything we could to make a living.

The change is so all encompassing it’s hard for even Gen-Xers like me to criticize. In a world where the costs of living keep going up; where gentrification pushes artists from their homes and studios; where all media is essentially advertising, what choice have we had?

The ‘90s idea of selling out is gone, but the phrase remains. Except now with a very different meaning. Selling out no longer means selling your soul in exchange for money. “Selling out” means the opposite: being validated by a close community of supporters.

It seems counterintuitive but it’s true. Think of lines around the block for streetwear drops and limited edition shoes. In a world where everything is infinite, limited quantities create meaning, attention, and desire. The people who get in are part of the tribe. If you miss out show up earlier next time.

The streetwear instinct for limited drops has its own roots in ‘90s culture — hip-hop, skateboarding, and their outsider status. The idea to do things limited, to intentionally craft a drop to make it special, if you know you know, echoes those ‘90s scenes.

Today those vibes are on hyperdrive and artificial scarcity is a game used to drive emotions at scale. Supreme could make as many T-shirts as they wanted but they’re worth more if they don’t. Scarcity inflates meaning and value.

The willingness to make that choice against market expectations of infinite product growth makes it meaningful to the people who get one. Even if it’s still another kind of marketing game, it shifts the target from mass to a kind of meaning.

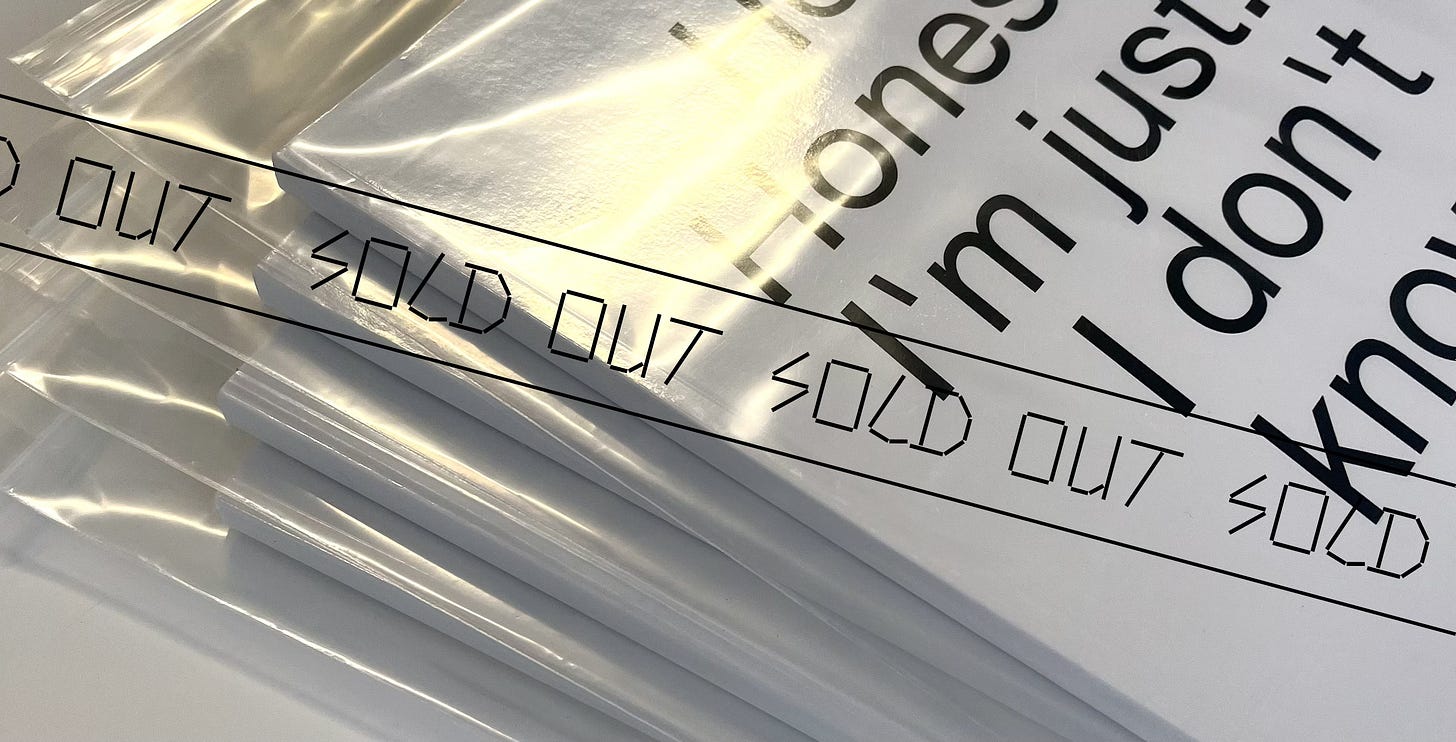

On Metalabel last Friday two releases sold out within hours of each other: a cassette edition of indie-dance group YACHT’s “New Release” (in just hours), and Zarina Nunes’s “Hey. Honestly, I’m just… I just don’t know.,” a zine we covered last week, shortly thereafter.

Both releases were limited editions. There were ten of Zarina’s book. There were 31 YACHT cassettes. They weren’t trying to generate the biggest return. They were making something that felt meaningful. As Zarina told us:

“I liked the idea of making small books that are accessible artworks. I’m not trying to make a ton of things or sell a ton of copies. I wanted to make it feel special.”

Same for YACHT. They made 31 editions priced at $20.31 because they joke their work is perpetually seven years ahead of its time (a blessing and a curse) — thus this album’s true release date is 2031. Their Metalabel collectors got to be in on the joke — and with unique edition numbers too.

The secret to selling out is making your release for the ones who will REALLY care about and treasure it. The other secret is that, done responsibly, it’s a way to reward ourselves too.

The feeling after a release sells out is euphoric. The kind of clear-cut validation that’s rare for creative people. When we’ve spoken with creators after their Metalabel drops have sold out they’ve felt celebrated and seen. We get to put our imposter syndrome aside and enjoy the moment.

But beware! We should not always aim to sell out. As we’ve learned from our friends, when selling out becomes the goal you put yourself in a trap. You stress the wrong incentives. You make yourself too tight. Selling out can be a validation but it can’t be the only goal.

What artists and audiences can do is celebrate making enough to reward a core audience and themselves. Make that our bar for success, not going viral.

By defining our own metric of success, we empower ourselves to tell our own stories. Our work can still be free and open across the internet while we offer “Director’s Cut” editions that invite people to explore and support us in more meaningful ways.

Earlier this year I released 250 editions of an essay and zip file that earned more than $1,000 from collectors. And sold out. It was an amazing feeling. Something I’d held onto for a long time felt validated in a deeply meaningful way. It remains one of my favorite things I’ve done. (I made a second open edition here.)

The ‘90s version of not selling out meant refusing to play certain spaces or not letting your song be in a beer commercial. The ‘20s version of selling out means making things in limited quantities to play against mass culture. Though different, the responses come from a similar place. They’re both sensing a culture where, to quote Claire L. Evans again, it feels like your life is a job and your house is a store. They’re looking for a way out.

We can get ourselves out by asking new questions when releasing our work: What would be the most meaningful for me and fun to others? How much of this release do I want to make collectible? What are New Media ways to make my work more exciting and more me?

So far on Metalabel we’ve seen people release limited edition essays and PDFs, physical books and art, and multimedia zip files that are tiny digital terrariums. Several of which have already sold out. Release by release, we’re exploring a new culture for how to express and show appreciation for each other’s work.

Member discussion