The Post-Individual

On the internet we can be whoever we want to be. We can choose from any number of qualities, real or imagined, and express ourselves and live our lives from that point of view online.

To go online is to become re-individualized — an individual in a whole new way and place. You still exist in the physical world, but you gain a new social existence that floats over-top of, around, inside of, and as a force within almost all other areas of life.

Because of the internet we don’t need to define our identity based on where we physically live, who we’re born to, or what we look like, as has been the case in human history until now.

The ability for people to separate themselves from their geographic, familial, and physical realities by creating new identities continues to reshape the world more than we realize. Computers and the internet have changed how we see and understand who we are, how we socialize, and inspired humans to act in ways closer to how algorithms and machines see us: segmenting the micro-personas and qualities within us into distinct alts and platform-specific identities that can take on lives of their own.

We’re in the midst of a significant evolution in what it means to be an individual. This experience and confluence of forces is what I call post-individualism — a term intended to capture the ways computers and the web have changed our sense of self and how society is changing in response.

While these dynamics are new, they echo the experiences of our ancestors that led to the creation of modern society as we know it, and even earlier societies too.

I. Kissing cousins and individualism

Our story starts more than a thousand years ago around 1000 A.D. when humans were going through a series of changes not dissimilar to what we’re experiencing now.

As recounted in two excellent books — The WEIRDest People in the World by Joseph Henrich and Inventing the Individual by Larry Siedentop, roughly 1,000 years ago was when the modern concept of the “individual” — someone with agency in what happens in their life socially, professionally, romantically, spiritually — gained momentum in Western society.

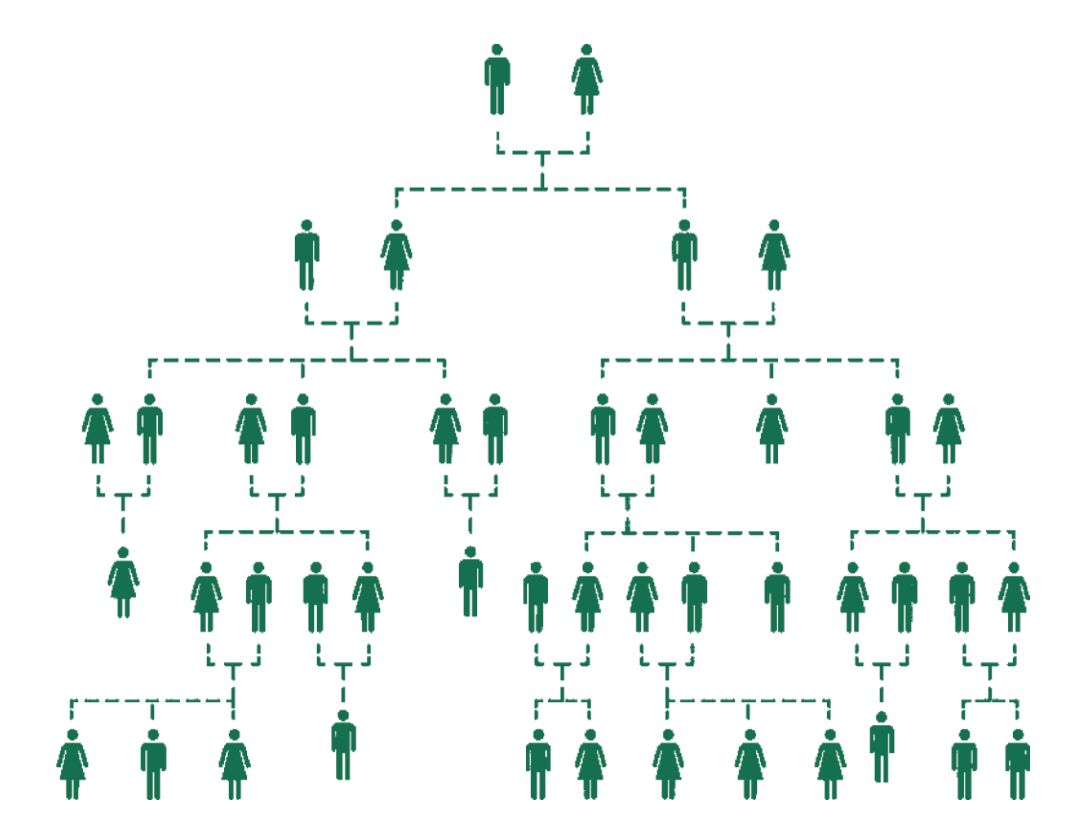

Before this turning point, civilization was less a teeming throng of diverse masses than a collection of closed miniverses bound by blood. The vast majority of people lived among extended families in clan-like settlements. As Henrich writes in WEIRDest People in the World, the family was the first religion. Who you were born to defined your whole existence.

Most people’s identities, belief systems, and paths in life were determined by who they were born to. People were members of clans and families first, individuals second, if at all.

One way families would preserve power was to marry cousins to each other. Yes — cousins. Cousin marriage reinvested the family's power directly into the future fortunes of the clan.

For centuries, cousin marriage was a dominant force. But about a thousand years ago, its prominence began to decline because of a surprising source: Christianity.

In the ancient world where wealthy and influential men held virtually all power and all others were seen as lesser beings, Christianity’s promise of universal salvation was a liberating secret that gave each person the right to their own inner purpose. As Christianity spread over the next thousand years, spiritual equality and, along with it, individualism did too.

Around 1000 A.D., Christian churches pushed individualism from the spiritual to the physical. Leaders of the Catholic Church, potentially intending to break the clan-based power that dominated their parishes in Southern Europe, issued a decree: it was forbidden for first cousins to marry.

Within decades, the custom of intra-cousin marriage began to decline. The structure of society changed along with it. For non-cousins to marry, places and ways for people to arrange marriages and find a partner were needed. New spaces and customs arose.

Within a century of the Catholic Church's prohibition, three major institutions of Western history became newly prominent: the city, the guild, and the university. All either had their growth take off (cities) or were largely invented (the guild and the university) within roughly a century of cousin marriage’s prohibition.

Some of the deepest foundations of modern society started because families weren’t allowed to marry first cousins anymore.

II. Individualism

What happened to those first individuals?

Neither Henrich or Siedentop’s books cite personal experiences documented by people living at the time, but seen through the lens of broader social changes that began in this era, we can make some educated guesses.

The rewards of individualism weren’t the right to be left alone, they were the right to choose who to align yourself with. The first individuals used their freedom to seek other people with whom they could live, work, love, raise families, and study. They (men, in particular) gained more sovereignty over their lives.

This need for alignment was critical because left on their own, early individuals were vulnerable. They risked being robbed, harmed, and exploited by others. They lacked easy entry to a trade. They were limited in what they could be or do.

As this process of people seeking safety and opportunity repeated generation after generation, trading posts grew into villages, villages became cities, and repeated interactions became institutions. The first university opened, attracted students, and gained influence. More followed. Guilds that provided a regimented path to work in the trades were established in increasing numbers of professions. As these institutions grew, more and more people left the countrysides for these bustling assemblies of individuals. Within centuries power shifted from the blood of clans to organizations of individuals, and the individual-driven system overtook the clan-based system it emerged from.

This process is why today disputes are settled by independent courts rather than family elders. It’s why I introduce myself as Yancey Strickler or just Yancey rather than Son of the Stricklers or however my ancestors said things. This isn’t true everywhere, but in many parts of the world today the family is less the focus than the individual because of these changes.

By the end of the 20th century this process played out to such an extent that people were expected to stand out on their own as individuals. To self-actualize as “Me” became the pinnacle of social success. The human experience became reoriented around an individual’s need to self-actualize through consumerism, as recounted in Adam Curtis’ documentary series The Century of the Self.

The force of individualism created a world of abundance for many. But in the most individualistic societies (the U.S., U.K., and Australia top the list) the costs included growing loneliness and the decline of social institutions. A 2021 study reported: “The role of friends in American social life is experiencing a pronounced decline… Americans report having fewer close friendships than they once did, talking to their friends less often, and relying less on their friends for personal support.”

We had reached this line of individualism’s final form: isolated, shrink-wrapped humans ready to self-actualize with each purchase.

III. Post-individualism and the self

This changed, like almost everything else, with the internet.

The internet opened up a new inner-outer virtual world where our thoughts were typed, confessed, searched, expressed, and manifested with the thoughts of others. A world where we became born again as individuals in a new realm.

No longer were we constrained by physicality or geography. We could be whoever we wanted to be. We could be however many we wanted to be. Our inner lives multiplied. This change came not just with the internet, but with the emergence of its underlying medium: the computer.

In 1984, M.I.T. professor Sherry Turkle published The Second Self, a sociological survey of the first computer users, including schoolchildren, secretaries, and stockbrokers in the 1970s and early ‘80s. Turkle observes from the very beginning that a computer wasn’t like a normal tool. Deborah, a middle school-age girl, tells her:

“When you program a computer, there is a little piece of your mind and now it’s a little piece of the computer’s mind and now you can see it. I mean, the computer can be just like you if you program it to be, your thoughts, your pictures, your feelings, your ideas, not everything, but a lot of things. And you can see the things you think and change them around.“

Turkle observes:

“Technology catalyzes changes not only in what we do but in how we think. It changes people’s awareness of themselves, of one another, of their relationship with the world. The new machine that stands behind the flashing digital signal, unlike the clock, the telescope, or the train, is a machine that ‘thinks.’ It challenges our notions not only of time and distance, but of mind… The question is not what will the computer be like in the future, but instead, what will we be like? What kind of people are we becoming?”

As the title of her book observes, computers and especially the internet change how people feel about themselves. They open up new notions of self and new forms of identity. In part because we learn to see ourselves the same way computers do.

Ben Thompson, author of the technology publication Stratechery, once illustrated in an essay how the internet had shaped his identity with a simple visual:

As an individual, Ben (the circle in the center) is the amalgamation of many distinct interests and identities. Each of the petals of the Ben-flower represent a part of his life and who he is. Because of the influence of social media, Ben sees these dimensions as identities to make distinct and further invest in. He writes:

“Separating my identities on Twitter does not mean a lesser experience, but a far superior one; social interaction in any medium is always a balance between self-expression and the accommodation of others, which means that in the analog world it is a constant struggle to strike a balance between being myself and annoying everyone around me at some point or another. The magic of the Internet, though, is that you can be whatever you want to be.”

Earlier generations were bound by family, geographic location, and their physical being. People today face few limits on their ability to explore, express, and manifest distinct identities. But our approaches are shaped by the platforms and algorithms we identiate through.

The spaces previous generations filled with close human relationships we fill with identities. This is how people are more connected than ever while being lonelier and having fewer close relationships than any generation in modern memory. We’re more connected to the many selves within us than we are to each other.

For individuals before the internet, the key existential question was “Who am I?” After the internet, it's “Who all am I?

IV. The post-individual

Classic individualism is a life-defining quest to establish who you are and to grow into that person over the rest of your life. But in a world where the quest for individualism can be started and repeated merely by logging on or creating a new account in a digital world, the meaning of this process has changed. As K-Hole put it in 2014’s “Youth Mode”:

“Once upon a time people were born into communities and had to find their individuality. Today people are born individuals and have to find their communities.”

This is the post-individual experience. It happens when someone accepts their individuality, but feels called for a variety of reasons (social, creative, metaphysical, financial) to seek greater meaning and context with others. Post-individualism isn't a rejection of individualism. It's a graduation from it.

People are not born post-individuals. Our social environments spark this desire for a specific kind of shared meaning. This especially happens online, where individuality creates the feeling of intellectual and emotional sovereignty, but also makes us lonely, thirsty for attention, and prone to being red-pilled by ideologies that aren’t true to our spirit or may harm us and others.

Like our ancestors 1,000 years ago, we're learning that leaving the safety of one’s real-world clan can be an isolating and dangerous experience. As I wrote in “The dark forest theory of the internet” in 2019, the web has become the place where powerful forces fight for influence and control:

“The internet of today is a battleground. The idealism of the ‘90s web is gone… The public and semi-public spaces we created to develop our identities, cultivate communities, and gain in knowledge were overtaken by forces using them to gain power of various kinds (market, political, social, and so on). This is the atmosphere of the mainstream web today: a relentless competition for power. As this competition has grown in size and ferocity, an increasing number of the population has scurried into their dark forests to avoid the fray.”

A thousand-plus years ago our ancestors's need for safety and context sparked the rise of cities, guilds, and universities. Our current needs as internet-liberated individuals are sparking a similar burst of organizational experiments, including the maturation of Reddit boards, Discord channels, WhatsApp and Telegram groups, and newer and repurposed forms of online communities. These are all post-individual proto-institutions that speak to the desire for safety, meaning, and social, creative, and financial prosperity we as online and offline individuals share.

Tellingly, these institutions are focused less on our entire selves than on aspects of who we are. Like content feed algorithms, the internet grants us the ability to segment our micro-personas into distinct identities that create and join communities with the micro-personas of others. On the internet our inner selves come alive to manifest parallel realities so powerful they’re overtaking the world that created them.

Evidence of the post-individual state is abundant.

- A new “whole self”: We know not to judge a book by its cover, but now we might not be able to entirely judge a book by its words either. As people learn to carry an increasing number of alts and slices of self, defining who we are becomes more complicated.

People are used to interacting with each other as surface-level individuals, but today we don’t always know how the physical person in front of us matches the multitudes within them. What if we discover the stranger is an ideological enemy we did not immediately perceive? How can we act without revealing the values of all our selves?

This larger “whole self” is why it can feel safer to interact online where everyone is in avatar mode than in physical environments where our identities are sometimes less clear. These are questions of inner and outer safety that generations today newly face.

- Post-individual collectives: In an era of individualism, how many followers you have is the key social indicator. In an era of post-individualism, it’s what groups you’re a part of that matters. The individual isn’t erased, it’s supported and strengthened by aligning with others. As more of our social and inner lives are lived online, internet-based groups will increasingly be how social value and power are attained. (See the classic Squad Wealth by Other Internet.)

Message boards and internet communities have existed since the start of the internet, but they’re becoming increasingly sophisticated. They now have the ability to raise funds, share decision making, and legally incorporate themselves. These internet-first organizations have already proven to be extremely influential online and off, and this will only grow. What the corporation was to the 20th century, online-first collective structures will be to the 21st. - Identityism: Post-individual dynamics and incentives lead to the proliferation of group identities. Many of these identities emerge through minute interests or points of difference between groups that create offshoots and factions. Micro-identities are a path to belonging.

Because our identities are tied to our core values and who we are, differences between or criticisms of ideals or members of our group can feel like criticisms and attacks on us. At times this resembles the clan-driven society that predated individualism with its many miniverses more than what we’ve known in recent centuries. - Memes: As in-group collective language and references, memes are a native form of post-individual communication. Learning one’s in-group language is a critical rite of passage that proves someone belongs. Memes are core internet communication that have already broken out of the web and embedded themselves deeply in everyday language. These post-individual signifiers reveal what tribes you're a member of and how deep your awareness extends.

V. The century after the self

In The Second Self, Sherry Turkle witnessed immediate changes in human psychology from the invention of the computer. As an interview subject told her:

“I like to think of my work as ‘out there.’ And I am ‘in here.’ The thing with the computer is that you start to lose track of the ins and the outs.”

I know this feeling first-hand.

For decades my identity has been in many ways internet-first. My professional development has been almost entirely on the web. I’ve been a longstanding member of several message boards. I have friendships with people all over the world that began and are sustained online that relate to different facets of who I am that the internet helped me discover. The internet is my social home.

I’ve experienced wonderful connections and discoveries from this. I’ve also experienced being on the fringe of so many worlds I don’t feel really part of anything. Moments when I’ve longed dangerously for attention. A lingering feeling of never really belonging anywhere except in front of a screen.

What I’ve come to realize is that while our potential identities are infinite, our energy is not. Energy put into one identity is energy taken from another. To be Very Online is to be Never Offline. To become infinite is to become infinitesimal somewhere else. As Turkle wrote in The Second Self:

“For adults as well as children, computers… offer companionship without the mutuality and complexity of a human relationship. They seduce because they provide a chance to be in complete control, but they can trap people into an infatuation with control, with building one’s own private world.”

This is something I'm still challenged by. But seeing myself as part of a larger tribe — a post-individual generation seeking meaning and clarity in a new world — gives the struggle context that's comfortingly bigger than just my experience.

This also isn't everyone's experience. It's most true for Very Online people who have allowed their self-identity and sense of self-worth to be tied up in these spaces. This is much less true for people whose lives are rooted in real-world communities. The state of the post-individual is not a default all experience the same way. It's a condition of environment. But as generations are increasingly born into digitally native social systems as Gen Z and younger are, the influence of the post-individual state will be an increasingly significant and perhaps welcome part of their lives.

As the journalist Adam Curtis told me in a conversation for The Creative Independent:

“The contemporary idea of freedom is very much an individualist one. I, as an individual, want to be free to do what I want to do… The idea of individual self-expression—whilst feeling limitless because the ideology of our age is individualism—looked at from another perspective is limiting because all you have is your own desires.

“The hyperindividualism of our age is not going to be going back into the bottle. You’ve got to square the circle. You’ve got to let people still feel they’re independent individuals, yet they are giving themselves up to something that is awesome, greater, and more powerful that carries them into the future beyond their own existence. That’s what people are yearning for.”

VI. The society of the selves

In Cinderella and Mrs. Doubtfire, identity conflicts are resolved by protagonists bringing their diverging personalities together. To marry Prince Charming, Cinderella must admit that it is she, a poor girl and not a princess, who the slipper fits. When Robin Williams comes clean as the boisterous matriarchal nanny, his children love him more.

According to Hollywood folk tales, merging your main and your alt is the moral thing to do. Is that the end game of the post-individual? To merge all our identities into one?

The activist and technologist Pia Mancini once told me about the emergence of a new word in Barcelona: yosotros— a combination of “I” (”yo”) and “We” (”nosotros”) that represents the collective I, the singular We. The term emerged through political movements, but its implications feel bigger. Could this represent a form of collective self? A new pronoun?

In 2021 the artist Katherine Ball told The Creative Independent:

“I use the pronoun ‘they’ in my bio… because I like this idea of recognizing that there are more microorganisms living in our bodies than there are of us. The body is an ecosystem. I think somehow, there’s another self, more ‘us’ than ‘I.’”

In a post-individual society of the selves, this could be a global subculture for how people come to define their identity.

When we bring in the developments of AI, even more significant changes to individuality appear. With most AI models being powerful amalgamations of incredible amounts of human-generated data, the notion of an individual mind could become a relic of the past. It’s striking to return to that comment from the middle school girl in the early ‘80s from The Second Self:

“When you program a computer, there is a little piece of your mind and now it’s a little piece of the computer’s mind and now you can see it. I mean, the computer can be just like you if you program it to be, your thoughts, your pictures, your feelings, your ideas, not everything, but a lot of things. And you can see the things you think and change them around.“

These changes can feel alarming. But if we go even further back in history, they could be bringing us closer to earlier roots. David Graeber and David Wengrow’s recent book The Dawn of Everything recounts how early Mesopotamian, American, and African societies moved between individualistic and collective periods based on how people procured food (hunting, individualistic; planting, collectivist) with a fluid complexity to identity and function:

“The freedom to abandon one’s community, knowing one will be welcomed in faraway lands; the freedom to shift back and forth between social structures, depending on the time of year; the freedom to disobey authorities without consequence — all appear to have been simply assumed among our distant ancestors, even if most people find them barely conceivable today.”

A frequent shift between individualistic and collective social systems is rooted in the human experience. But the dominance of modern institutions created top-down, hierarchical structures we've forgotten are meant to change.

And now they are.

At this very second, message boards, group texts, social media, dark forests of the internet, and other digital worlds are challenging institutions coded a thousand years ago. The 21st century and perhaps many future centuries will be heavily influenced by post-individualistic, internet-based principles about what a self really is. Online communities have already evolved from one person one vote to one identity one vote. How distant the Victorian Age feels to us now will be what life before the internet feels like for generations to come.

The internet's infinite private worlds at times feel more like the clan-based societies that predated individualism. But where past worlds were bound by blood, today’s are bound by interests, desires, identities, and what the algorithms governing these spaces — helmed by capitalistic KPIs —nudge us to do.

If the experiences of past generations are a guide, what lies ahead isn't the collapse of civilization. It's the invention of a new one based on a very different idea of what it means to be an individual.

Thank you

Thanks to Adam Curtis, John Higgs, Pia Mancini, Priya Parker, Elizabeth Anderson, Heather McGhee, Jamie Kim, Brandon Stosuy, Clare Farrell, and Charlie Waterhouse for conversations that helped shape this piece.

Thanks to Joseph Henrich, Larry Sidentop, David Graeber, David Wengrow, Sherry Turkle, Katherine Dee, Ben Thompson, Visakan Veerasamy, K-Hole, and Aaron Lewis for their writings that helped inform these ideas.

Thanks to Ilya Yudanov and Laurel Schwulst for creating visuals in this piece.

Linknotes

The WEIRDest People in the World by Joseph Henrich

Inventing the Individual by Larry Sidentop

The Century of the Self by Adam Curtis

The Second Self by Sherry Turkle

The Dawn of Everything by David Graeber and David Wengrow

Social Networking 2.0 by Ben Thompson

Youth Mode by K-Hole

Adam Curtis on the dangers of self-expression in The Creative Independent

Katherine Ball on striving to be an amateur by The Creative Independent

Multiple Personality Disorder, or D.I.D., seems prevalent online by Katherine Dee

Being Your Selves: Identity R&D on Twitter by Aaron Z Lewis

My notes from reading from Sherry Turkle’s “The Second Self”

Provenance

This essay started in 2019 and was completed in late 2023. It was written in Los Angeles, Vancouver, London, and New York City.

It was first published in The Dark Forest Anthology of the Internet in 2024 by The Dark Forest Collective.

"The Post-Individual" was released as a standalone single through the Dark Forest Collective that included a video introduction, an audio recording of the piece, and research notes in April 2024.

That first edition was supported by 250 collectors. They include:

Aaron Cohick, Alberto Colpo, Alfatih, AliaK, Alicia Peyrano, Alvaro Delgado, Alyssa Feuerer, Andrea Neustein, Aron, Brad Barrish, buffets.eth, Chase Wade Snyder, Clifford, Dallin Skinner, David Dennis, Diego Cobo, Dominic Rishe, Eóin MacManus, esdotge, farcaster.id/na, Fraser Stanley , Gareth I. Jones, Gavin Becker, Gilbert Again, Giovanni Pigliacelli, Itay Dreyfus, James Biles, James Teng, Jason Glickman, Joe Carpita, Johannes Kleske, Jonathan Tanners, Jon-Kyle Mohr, Joshua Citarella, Lukaszgraphz, Maarten Walraven, Martin Willers, matthijs_ideas, Melissa Kadri, misha de ridder, Morgan Howard, Nat Emodi, Nate Sarsona, Nikolai Kirilenko, Olle Strandberg Colling, Patti Hinman, Pet3rpan, Pete Deevakul, Philippe Larochelle, Povuh, Qsteak, Robert Lin, Sam Mason de Caires, Sara Campbell, Sari Azout, Severin Matusek, Stephen Sentelle, Tatiana Mondragon, Totholz5d, Vicki Tan, Vishal, Waqas Ali

Discussion